|

2.16.03

2.16.03

j: To Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC). Formely known as Saigon, before North Vietnam "liberated" the South on April 30, 1975 and renamed it in honour of Ho Chi Minh. Saigon is still used today, though technically it refers to the central "District 1" area of HCMC. We later found out on a tour that one example of where Saigon is used officially is for beauty pageants, since "Miss Ho Chi Minh City" just wouldn't fly. The US dollar operates in parallel with the Vietnamese dong, at a roughly 15,000 dong to the dollar conversion rate. When I quote prices in dollars only, it's because that's the way it was quoted and paid. The ATM dispensed a maximum of 2 million dong (roughly US$134), often as a wad of forty 50,000 dong notes -- see the photo to the right. The guidebook quips regarding lottery tickets that if you win, you too can become a dong millionaire! Since there are no coins -- quite nice, actually -- there are no vending machines and public phones only take phonecards.

h: Smile on, Saigon.

Jan and I flew into what is now called Ho Chi Minh City and the first thing we hit getting off the plane was a virtual sea of black heads all standing in lines to pass through immigration. One huge room, 16 or so lines and all of them several persons wide. There seemed to be virtually no movement for ages, and the air was getting frighteningly stale when sudden the pace seemed to pick up and we were finally making our way to the baggage claim.

h: Smile on, Saigon.

Jan and I flew into what is now called Ho Chi Minh City and the first thing we hit getting off the plane was a virtual sea of black heads all standing in lines to pass through immigration. One huge room, 16 or so lines and all of them several persons wide. There seemed to be virtually no movement for ages, and the air was getting frighteningly stale when sudden the pace seemed to pick up and we were finally making our way to the baggage claim.

Standing on the inside of the terminal looking out was intimidating. Again, a sea of black heads awaiting various arrivals of friends, relatives, customers. Walking down the aisle lines with waiting people reminded me of those Hollywood film premiers with the red carpet and fans lined along either side as the stars make their way from their limo to the building entrance. The guide book instructed us to take a metered taxi to the part of the city where we could expect to find cheap accommodation so as soon as we made our way past the proverbial red carpet we were inundated with taxi offers. We picked one somewhat at random and set out.

I looked out the window at the city as we sped through the streets and instantly liked it better than Bangkok. Perhaps it was merely that I decided to, perhaps it was the clean air and clear skies, perhaps it was the absence of grime, perhaps it was the lack of suffocating skyscrapers, perhaps it was the brightly painted buildings.

Or perhaps it was merely the stunning full moon that was looming over the horizon. Iíve always been a sucker for a full moon.

We arrived at the hotel of our choice which was full, but our hostess kindly escorted us across the street to her friendís hotel Ė which has turned out to be most suitable. Itís family run, a father and son run the desk and the mom brings up a fried-egg and Vietnamese coffee in the morning for each of us, included in the room price. Thereís a little balcony with French doors that overlooks the very noisy street. Itís not spotlessly clean but it has character.

|

|

2.17.03

2.17.03

j: Saigon. Monday was a rest and get caught up kind of day. Check out the available tours, buy a few snacks and drinks at the grocery store, find a good Internet cafe, that sort of stuff. The day started with in-room-served breakfast, included in our US$12 nightly room rate, pre-ordered the night before for 9:30am. For me, a tasty "omelette" consisting of 2 fried eggs with lots of butter and salt and pepper, plus a delicious Vietnamese white coffee, meaning 1/3 condensed milk and drip-filtered into the cup at our "table." With all that condensed milk there was no need to add sugar. Our lunch was unexciting, at the address where a guidebook-recommended restaurant was supposed to be, but was either renamed or nonexistent. Or moved, a few doors down the street, as we discovered after our meal -- doh! For dinner we made our way back to the restaurant that had moved on us, one staffed (and owned?) by deaf people specializing in the distinct haute cuisine from Hué, a coastal town about half way up the country. Dinner was excellent and ridiculously cheap: 60,000 dong (US$4) for a soup, two entrees and two non-alcoholic beverages. The waitress even demonstrated to us how to eat our meal, since you were supposed to put a little bit of each plate into our little individual rice bowls using the ceramic spoons, then eat from our bowls using chopsticks. I had banh khoai, a type of omelette with chicken and bean sprouts. Hmmm, food and drink seem to loom large on this trip!

|

|

2.18.03

2.18.03

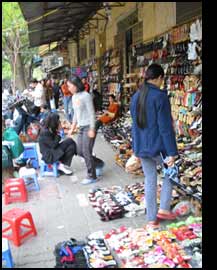

j: On Tuesday we walked to the more upscale Dong Khoi area, intending to look at some of the nicer older-with-character hotels. We wanted to take a taxi, but we seemed to have trouble finding one once we got a block outside of our tourist ghetto. We ended up passing the main covered market, in which we stopped briefly, buying some cashews -- excellent snack food by the way, containing protein and fat to keep you going. We then figured we could walk the rest of the way, another 10-15 minutes. On the street outside of the market, the vendors were significantly more persistent than others we had seen so far. We did hear the crunch of two motorcycles colliding about 30m behind us, and sure enough one motorcycle was lying in the middle of the road lane and the other one had pulled off to the side. No serious injuries, but true to form as explained in the guidebook, they stood in the middle of the street arguing over whose fault it was ("it" being potentially "squashed chicken" as our guidebook humourously put it), not bothering to move completely to the side, and attracting the attention of pretty much everyone in the vicinity. Owing to our late start, we pretty much headed straight to lunch, picking a restaurant that was more expensive than we expected, but had well prepared food and attentive service. Afterwards we walked past the People's Committee Building (no tourists allowed inside) and into the Museum of Ho Chi Minh City, a former palace building housing artefacts from the communist struggle for power in Vietnam. The model of the famous Cu Chi tunnels was handy as we had decided not to do the half-day tour to see the real thing -- which we later heard from other tourists was interesting but very claustrophobic and involved crawling on one's knees in the dark, despite the 150m of tunnels having been widened slightly for tourism. Otherwise the museum was information overload for me. An interesting side-note was that there were many wedding-couple photos being taken inside the building and in its gardens, which we thought might be a photo shoot. I asked one of the aides in my extensive Vietnamese, tap chí, meaning "magazine" (who needs full sentences and grammar in situations like these?) to which she replied no. After this non-air-conditioned museum, we walked a whole block before stopping for cake and iced coffee -- did I mention it was hot? At least it wasn't humid, so it was bearable in the shade. At this point a taxi ride back to the hotel (15,000 dong or US$1) was in order, to rest up before dinner.

Random side note: the Ð letter in Vietnamese appears to be the same as the capital "Eth" in Icelandic, though the lower case versions are slightly different. And yes, there is a difference between "Ð" and "D" in pronounciation -- the former sounds like a "d", whereas the latter sounds like a "y" in the South and a "z" in the North. While were on the subject, Vietnamese is a tonal language with six tones versus Thailand's five, and has a few North/South pronounciation differences. Very hard for Westerners like me. And each pronounciation guide I have is different and not all that accurate, or so it seems.

Heather chose walking along the Chinese canal and Saigon river for dinner back in Dong Khoi. We walked south towards the canal, passing within a few blocks a small evening street market that was not mentioned in our guidebooks or tourist map, hence the lack of tourists. Heading parallel to the river, we passed a night seafood market, with large buckets full of wriggling fresh seafood, getting splashed by cars driving along the somewhat dark wet street, and absolutely no tourists in mind. Interesting experience, though not what we had expected, so we had better back to the better lighted street. We passed one intersection full of street vendors and restaurants spilling out into the sidewalks, every table full, and again no tourists. Walking along the Saigon River wasn't all that exciting either, except for the insanity that is crossing the street as a pedestrian. Yep, there's nothing like standing on the very faded center line at night while cars, motorcycles and large trucks go zooming by, being thankful at least one of us is wearing a white shirt for visibility. Dinner was ok, but was full of tourists only, and at over twice the cost of the previous night's meal, was no better. Slightly annoying (though forewarned in the guidebook) was their placing a small plate of fruit on the table at the end of the meal, and then charging us 20,000 dong (US$1.33) for it -- not a princely sum, but deceptive nonetheless. In comparison, the next night we would order a mixed fruit plate that was 3 times as large for half the price, and in Mûi Né we were given a small plate of fruit for free at one particularly friendly restaurant. But I get ahead of myself. After dinner we walked passed the People's Committee Building again, which was supposed to be covered with "thousands of geckos" at night -- we saw dozens, but certainly not thousands nor even hundreds. Then we walked a few blocks to the Ho Chi Minh City museum (again!) to check out the park across the street, where a makeshift cafe and folk-music stage were supposed to be. Well, they were there, but it wasn't exactly folk-music, more like bad pop music. Home, James.

Heather chose walking along the Chinese canal and Saigon river for dinner back in Dong Khoi. We walked south towards the canal, passing within a few blocks a small evening street market that was not mentioned in our guidebooks or tourist map, hence the lack of tourists. Heading parallel to the river, we passed a night seafood market, with large buckets full of wriggling fresh seafood, getting splashed by cars driving along the somewhat dark wet street, and absolutely no tourists in mind. Interesting experience, though not what we had expected, so we had better back to the better lighted street. We passed one intersection full of street vendors and restaurants spilling out into the sidewalks, every table full, and again no tourists. Walking along the Saigon River wasn't all that exciting either, except for the insanity that is crossing the street as a pedestrian. Yep, there's nothing like standing on the very faded center line at night while cars, motorcycles and large trucks go zooming by, being thankful at least one of us is wearing a white shirt for visibility. Dinner was ok, but was full of tourists only, and at over twice the cost of the previous night's meal, was no better. Slightly annoying (though forewarned in the guidebook) was their placing a small plate of fruit on the table at the end of the meal, and then charging us 20,000 dong (US$1.33) for it -- not a princely sum, but deceptive nonetheless. In comparison, the next night we would order a mixed fruit plate that was 3 times as large for half the price, and in Mûi Né we were given a small plate of fruit for free at one particularly friendly restaurant. But I get ahead of myself. After dinner we walked passed the People's Committee Building again, which was supposed to be covered with "thousands of geckos" at night -- we saw dozens, but certainly not thousands nor even hundreds. Then we walked a few blocks to the Ho Chi Minh City museum (again!) to check out the park across the street, where a makeshift cafe and folk-music stage were supposed to be. Well, they were there, but it wasn't exactly folk-music, more like bad pop music. Home, James.

h: Okay, so I have no idea who this James guy is... but weíve been in Ho Chi Minh City for two full days now and I am still as charmed, if not more. The city is colorful and more European in design Ė buildings are walk-ups and seldom surpass 6 stories. The streets are a nightmare beyond comprehension Ė filled with motorscooters and motorcycles that swarm through the streets like bees from a hive, fluidly in motion together but with individual movement still visible. Crossing the street is an exhilarating experience Ė there are seldom crosswalks and lights so in general you must weave in and out of passing motorists as you cross one lane of traffic, then pause in the center to naviagate the opposing lane of traffic.

So why do I like Saigon so much better? Iíve had two days to contemplate it and in addition to all the things I mentioned above about the lack of air pollution and resulting building grimeÖ I think what I really like is how it doesnít feel so rehearsed. Thais by comparison have been catering to tourists for much longer and in many ways you could say they are much better at it. That is, in terms of getting what they want from tourists, they are skilled. But when you visit a country and nearly everywhere you go it seems you only encounter people who are accustomed to dealing with tourists, well, you get this bad taste in your mouth that everything youíre seeing and doing is staged. In some cases it is, but ironically in Thailandís case, you are seeing the real Thailand in this respect. Thailand attracts 10 million visitors a year, and the revenue generated by the foreign dollars spent here have allowed for economic growth that most Asian countries can only dream of. Tourism is the real Thailand, you might say; itís how they earn their living and itís a major source of revenue and a prominent industry.

So why do I like Saigon so much better? Iíve had two days to contemplate it and in addition to all the things I mentioned above about the lack of air pollution and resulting building grimeÖ I think what I really like is how it doesnít feel so rehearsed. Thais by comparison have been catering to tourists for much longer and in many ways you could say they are much better at it. That is, in terms of getting what they want from tourists, they are skilled. But when you visit a country and nearly everywhere you go it seems you only encounter people who are accustomed to dealing with tourists, well, you get this bad taste in your mouth that everything youíre seeing and doing is staged. In some cases it is, but ironically in Thailandís case, you are seeing the real Thailand in this respect. Thailand attracts 10 million visitors a year, and the revenue generated by the foreign dollars spent here have allowed for economic growth that most Asian countries can only dream of. Tourism is the real Thailand, you might say; itís how they earn their living and itís a major source of revenue and a prominent industry.

Vietnam can only aspire to such revenue from tourists. In fact, the government-run Vietnam Airlines in-flight magazine goes so far as to name Thailand as a model for what it hopes to achieve. But I gotta tell you that while the need for revenue is evident, I wish they could find it elsewhere.

You walk down the streets here and occasionally people try to sell you cigarettes or a pedicab ride, but a shake of the head seems to suffice in most cases and somehow you just donít feel like the scene youíre looking at gravitates around trying to sell you something. People actually live here and you see them all around doing their daily stuff. Like KL and Bangkok there are still the T-shirts, watches, and bootleg CDs but thereís also something I didnít see much of in those other cities. Art. Everywhere. There are art stores all over the place, with their colorful reproductions of European masters and original tradition Asian scenes spilling into the streets. In the lobbies of inexpensive hotels are carved hardwood chairs inlaid with mother-of-pearl. Several members of my extended family were in the military at different times and many of them brought back with them various pieces of Asian art, some of it better withstanding the test of time than others. But I can see what charmed them into wanting to bring some of it home with them Ė it gladdens the heart to see such the colors and expression spilling into the streets.

I think the sum of it is that poverty and lack of sanitation depresses me but I am offered some relief if there is character. Bangkok and KL very much lacked what I would call character Ė two modern cities spewing and speeding along but with no soul.

|

|

2.19.03

2.19.03

j: OK, some "real" sightseeing today and we even set an alarm for our 7am breakfast. We grabbed a taxi and headed out to the Jade Emperor Pagoda, a colourful Buddhist pagoda that, oddly enough, is not in Chinatown. We never did make it to the Saigonese Chinatown known as Cholon. Then a longish slog in the heat along streets and through a lovely park containing penguin-shaped trash bins -- why penguins, we don't know, nor did we ask. Our next stop was "Binh Soup Shop" (binh means peace) for some delicious noodle soup known as pho (prounounced "fur", but I could not spell it here with the correct marks on the "o"), practically a national symbol. What makes this place special and a bit of a tourist attraction, although we only saw one other table of people there, is that above this shop was a secret headquarters of the VC in Saigon, and here they planned the attack on the US embassy during the Tet Offensive in 1968. The owner was jailed and tortured by South Vietnamese for 8 or 9 years, but since reunification in 1975, he has been back running his soup shop. Well, maybe he just eats there now and his children run the shop -- we did actually see him there (I was actually waving to the staff to get their attention for a drink we hadn't received yet, but they thought I was gesturing to ask if that man was the man), though we didn't talk to him as many former GIs do. Now that museums were re-opened after lunchtime, we hopped into a taxi for a short ride to the Reunification Palace, another historical site. It was here that on April 30, 1975 South Vietnam ceased to be, as two tanks drove through the iron gates, and a soldier ran to the rooftop to unfurl the "liberation" flag. This palace looks like a 60's era concrete ugly building, not evoking the grandeur that the word "palace" does in my mind. The guided English tour was nice, but the longish video at the end was more informative, and pretty much killed our "enthusiasm" for going to the War Remnants Museum, also known as the War Crimes Museum, which pretty much shows the horrors of war inflicted on civilians, something of which I did not need convincing. Maybe George W. Bush should go see it. One fascinating fact for me is that the Vietnam war is known as the "American War" here in Vietnam. That, plus hardly anyone speaks French anymore, which is not too surprising given that the French were evil colonialists, but my high-school math teacher had been a French-speaking Vietnamese so that shaped my assumptions. Nor is fluency in Russian valued anymore, in case you were curious.

So we did what any hardy adventurous tourist would do -- headed for cake and iced coffee in an air-conditioned cafe. No no, don't feel sorry for us, really. For dinner we returned to that haute cuisine restaurant for another delightful meal, then, what else, camped out on email and the Internet again, party animals that we are. Besides, our bus tour the next day would leave at the cruel time of 7:30am, which meant packing up tonight to maximize sleep. OK, now you can feel sorry for us :-) We did decide that we would return to our hotel after our 2-day tour, even though the spotless one across the street would be available, because (a) the guy had been really nice, and (b) we thought leaving our baggage at the hotel would be safer, or at least more convenient, than the tour company.

|

|

2.20.03

2.20.03

j: To the Mekong Delta. After another delightful little breakfast eaten on our 2nd floor balcony, we grabbed our little day knapsacks and hustled on down to our tour company office around the corner in the nick of time to wait an extra ten minutes for the minibus. When it showed up, half full of passengers already, a tour guide announced "2-day tour" (that's us!) and we settled into some seats. The guide, H&ocute;a, was quite humourous and spoke English very goodly. Just kidding, his English was good, though sometimes a little hard to understand -- but he sometimes spelled the English word when it was the key point he was making, just to be sure. He gave us the history of Saigon as we snaked through traffic, including that aforementioned tidbit about beauty pageants, and noted that Ho Chi Minh City had 2,000,000 motorcycles in a city of 6-8 million people. Then his mobile phone rang, and we pulled off to the side of the road to wait for a motorcycle-delivered Danish couple who had missed the bus. "Slept in?" he asked them -- no, they just hadn't heard him announce the two-day tour departure, which must have been true since I remembered seeing the couple waiting at the tour office. This tour company runs 1-day, 2-day, 3-day, 4-day and 5-day tours to the Mekong Delta, as well as boat trips up to Phnom Penh in Cambodia. They must be well organized, as the various multi-day trips overlap and intersect each other, so that the tour group can be split up at certain points, as well as get combined. Their big whiteboard in the office lists nationality and number of people of each party departing on each type of tour for the next few days.

About 3 hours later we arrived in some small town in the Mekong Delta to embark on what would be our first of many boats. We wound our way through medium-sized rivers, canals, smaller rivers, even a 1.5km (1 mile) wide branch, the largest of nine, of the Mekong river. We went by a small wholesale floating market, where vendors hung fruit and veggies from the top of 10 foot bamboo poles to advertise their wares. We stopped several times in food-making operations, such as delicious coconut candy with the consistency of toffee, rice krispies made from popped rice similar to popcorn, and a distinctly non-edible ceramic factory. Interestingly, coconut shells are used for firewood, as are rice husks. We stopped for an inexpensive set-plate lunch in a little village, where I also took one of the free one-speed mountain bikes (!) for a little spin through the village and down country roads. Now I know what it feels like when bicycle pedals are bent -- they move elliptically or something like that! Woohoo! At least I didn't crash, it didn't break down, and it was still better and faster than walking.

About 3 hours later we arrived in some small town in the Mekong Delta to embark on what would be our first of many boats. We wound our way through medium-sized rivers, canals, smaller rivers, even a 1.5km (1 mile) wide branch, the largest of nine, of the Mekong river. We went by a small wholesale floating market, where vendors hung fruit and veggies from the top of 10 foot bamboo poles to advertise their wares. We stopped several times in food-making operations, such as delicious coconut candy with the consistency of toffee, rice krispies made from popped rice similar to popcorn, and a distinctly non-edible ceramic factory. Interestingly, coconut shells are used for firewood, as are rice husks. We stopped for an inexpensive set-plate lunch in a little village, where I also took one of the free one-speed mountain bikes (!) for a little spin through the village and down country roads. Now I know what it feels like when bicycle pedals are bent -- they move elliptically or something like that! Woohoo! At least I didn't crash, it didn't break down, and it was still better and faster than walking.

Late in the afternoon I climbed on the roof of the boat to stretch out and take my shirt off in the breeze, enjoying the scenery reminiscent of the river boat trips in the "Apocalypse Now" movie. I chatted with an American guy, one of few that we met, who had recently been in Cambodia and really liked it. Towards dusk we arrived in Can Tho, the largest city in the delta. Our hotel, included in the tour, was a few minutes walk from the waterfront, down a little alley full of people's homes. The room was clean and comfortable, with fan and bathroom but no hot water. After a little rest, we met the group again in the lobby to head out for dinner at a local restaurant. I tried the complimentary shot of "snake wine," which is potent rice wine (stronger than Japan's sake) bottled with venomous snakes, usually cobras. I also tried the stir-fried snake, a local specialty, which of course tastes like chicken :-) We chatted with an Italian couple in a combination of English, French and Spanish, as well as an interesting overseas-Vietnamese father and daughter pair from Seattle. Then it was back to hotel and an early bedtime, as our wakeup call would come at 6:30am the next morning.

h: I have two impressions which resonate from this tour; one is of the mud, endless mud, that is this world-class river delta. I watched the locals along its banks doing what locals do: fishing, bathing, washing dishes. It struck me that what these people know first and foremost is mud. The water is a way of life for them and they are infinitely adept at manipulating it to do their bidding - from irrigation to transportation. But this is common throughout the world since having come from the ocean man seems to have always been inclined to living in and among the oceans, lakes, and rivers of the world. But unique to an immense delta like this... is the mud. The mud just IS. It is everywhere, it never goes away, and the river continually brings more and more of it. There is always mud and what I find fascinating is that this is all these people know. Imagine living your entire life where there is no dry season, there is no world without mud. Perhaps that seems a useless thing to dwell on, insignificant at best, but for me it seems to sum up the antithesis of the life I am currently living; a life of endless variety and with a sampling of virtually every season, every climate, every landform.

h: I have two impressions which resonate from this tour; one is of the mud, endless mud, that is this world-class river delta. I watched the locals along its banks doing what locals do: fishing, bathing, washing dishes. It struck me that what these people know first and foremost is mud. The water is a way of life for them and they are infinitely adept at manipulating it to do their bidding - from irrigation to transportation. But this is common throughout the world since having come from the ocean man seems to have always been inclined to living in and among the oceans, lakes, and rivers of the world. But unique to an immense delta like this... is the mud. The mud just IS. It is everywhere, it never goes away, and the river continually brings more and more of it. There is always mud and what I find fascinating is that this is all these people know. Imagine living your entire life where there is no dry season, there is no world without mud. Perhaps that seems a useless thing to dwell on, insignificant at best, but for me it seems to sum up the antithesis of the life I am currently living; a life of endless variety and with a sampling of virtually every season, every climate, every landform.

The second impression is somewhat more personal. We had in our tour group two different people who had left Vietnam as refugees and had returned to see what had been their culture and country. There was a woman now from Sydney who was travelling with her teenaged daughter and there was a man and his high-school-aged daughter, Trung and Vienna, from Bellevue, Washington. Just across the lake, for those of you not acquainted with my fair city, Seattle. Small world.

While Jan was strutting his stuff at dinner in French, Spanish and English with the Italian couple, I had a really good time talking to Trung and Vienna; it was nice to touch base with someone who hadn't been away from home for quite so long as we had. But because Trung spoke Vietnamese and because of his unusual perspective having met him gave that part of the trip infinitely more depth for me. At one point he was talking to the "first mate" of our boat; that particular boat, I learned from Trung's conversation, was run by a young man and his sister who were paid each 20,000 dong per day (about USD $1.30) for the boat services they provide the tour company. This 20,000 dong, according the young woman was enough to buy daily meals of rice, and occasionally but not always some meat to go with it. They live hand to mouth, no savings, and are paid daily.

Jan and I were pretty appalled that they make so little and felt a certain indignation that our tour company would pay its help so poorly. But in retrospect, the cost of the tour was so small that unless they raised the price of the tour (making themselves less competitive in the long run) it would be easy to see how the tour fees must be divided infintitely among the different people involved. Bus drivers, boat helmsmen and crew, guides, tour office staff - all of which exist in multiplicity on a given tour.

Jan and I were pretty appalled that they make so little and felt a certain indignation that our tour company would pay its help so poorly. But in retrospect, the cost of the tour was so small that unless they raised the price of the tour (making themselves less competitive in the long run) it would be easy to see how the tour fees must be divided infintitely among the different people involved. Bus drivers, boat helmsmen and crew, guides, tour office staff - all of which exist in multiplicity on a given tour.

I was somewhat shy to ask Trung about his experience of returning to Vietnam after all those years and such a dramatic departure. I could only think of how emotional it is for me to return to my own childhood town and how it must pale in comparison to leaving everything you have ever known - family, friends, language, culture, food, everything - behind in a moment and staring an entirely new life. Jan, on the other hand, seems suited for a career in journalism and has no difficulty putting forth such questions to people. Trung told us his family had one day to prepare and when they gathered together all the money they had between them it totalled less than USD $20. They were put on a plane with other families and shipped around to a few cities in SE Asia before they landed as refugees in Los Angeles. There, they were hosted by a family for a few months and within a few weeks they had jobs and were learning English. Trung has made an amazing life for himself in Seattle and is truly living what you might call the American dream, but he said perhaps the hardest thing was wondering what had happened to all the people he had known, people that didn't leave.

|

|

2.21.03

2.21.03

j: A quick shower and no real bags to pack (remember we just had our knapsacks with a change of clothes, not the full backpacks) brought us downstairs for the 7am breakfast, and out the door with the tour group at 7:30am sharp. We walked back to the waterfront to hop on a different boat; first stop, the floating market. The biggest floating market in the delta. At first we tied up to a pineapple vendor, who proceeded to drag anchor almost back into another boat, so we motored forwards a ways to re-anchor -- I mean, it's not like there are marked parking spaces in this crowded river market. As the little rowboat took half the tour group onto a little mini-tour of the market, I bought a whole fresh pineapple, peeled and de-eyed, for a whopping 3,000 dong (US 20 cents). Incroyable. A little fibrous, but nicely sweet, these are the best pineapples in Vietnam we were told. Then we took our turn in the rowboat -- the floating market was indeed large, but unfortunately not that colourful, especially as it was difficult to look into the larger dark boats sitting down in a small rowboat, though again the bamboo poles displayed samples of each boat's wares. Afterwards we stopped in a rice-paper-making "factory" as well as a rice "factory" where an antiquated machine separated the rice into its components: the husk, used as fuel; the bran; brown rice for export or polished white rice for domestic use; and "broken rice" which is certainly an apt description. We also disembarked the boat in a small village for a lovely, relaxing, partly-shaded 40-minute canal-side walk, where we could see a variety of fruit trees up close, as well as some of the older single-wooden-plank "monkey bridges" that the government is trying to replace with concrete foot bridges.

For lunch we returned to the city of Can Tho and another group meal where I tried stir-fried frog, which again tastes like chicken, though with many small bones. I later read in the guidebook that frogs and snakes are exotic animals that should not be eaten, including avoiding snake wine... oops, I really should read the general information section before arriving in the country! A strange Dutch woman on our tour kept asking if the frogs were farm-raised, or just plucked from the foul murky waters -- some things are better left unanswered. After lunch we boarded another boat for an hour ride back to the minibus, which would take another 4 hours to get back to Saigon. I couldn't imagine doing a one-day tour, with its 7 hours of bus compared to about 4 hours of boat trip -- which is what the last 5 picked-up-and-crammed-in passengers had done. Like I said, the tour company was efficient in that regard. I chatted some more with the Italian couple, who gave us some pointers regarding Mûi Né, where they had recently been. This 2-day tour, including hotel but no meals, cost a hard-to-believe grand total of US$15 each. It seemed we were the only people to tip our guide as we finally descended from the bus back in Saigon, and he smiled greatly at us in appreciation.

That evening our backpacks were waiting for us in our room, this time up on the 4th floor, which may not sound that far up, but without an elevator and the windowless half of the rooms' air-conditioners venting hot air into the stairwell, it was a bit of a hike. We figured pizza sounded good for dinner, as a break from the Vietnamese food. Some more Internet action to firm up our hotel plans for Mûi Né and again early to bed, early to rise, as our bus would leave at 7:30am. Again.

|

|

2.22.03

2.22.03

j: To Mûi Né. After another delightful little breakfast eaten on our 4th floor balcony, we hustled on down to our tour company office around the corner, parking Heather with the luggage while I hustled to the ATM to beef up our dong reserves. The bus ended up being 15 minutes late, quite full after we loaded on, and for no apparent reason circled the block twice before leaving for the 4 hour, US$6, drive to Mûi Né. As is often the case, we ended up pulling the curtains closed to block out the sun, esp. since the air-con was not that effective, and people pretty much gave up on it and opened windows for the breeze. As we approached our downtown-less destination, we realized that the driver had not asked us which hotel we wanted to be dropped off at. Hmmm, how would that work with 40 people on the bus anyways? As we cruised along the only road in "town," the names of hotels and resorts slid by, including our "Sailing Club" resort. After a few minutes we stopped at a cafe, where the driver's assistant explained that if we had reservations to tell him the hotel name so that we could be dropped off, and if we didn't, then they could suggest a few places; also, those continuing on to the next city could have lunch in the cafe to while away the next hour and a half before the bus continued. On the way back to our hotel, the bus stopped at a couple of small hotels, where people jumped off to check them out while the bus continued with their luggage -- for the bus would return in 10-15 minutes to pick them up or to give them their bags. I would think that would be a little disconcerting to watch the bus pull away with your backpack. Just after noon we were dropped off at our resort, where we relaxed with a pool and beachside patio drink while waiting for a room to be prepared. This resort had just opened the previous August by an Aussie couple, so it was very clean and nicely landscaped and bug-free. I guess the near-constant wind has something to do with that last point, as well as making this a popular kite-surfing spot and providing lots of waves to play in. More expensive than our usual digs, but it was time for some serious relaxation and we gave ourselves this little treat.

For dinner we went practically across the street to a little restaurant, where two bowls of passable pho, a soda and a Vietnamese tea came to a whopping 23,000 dong (US$1.50) before tip, which ironically was less than the 30,000 dong a single mango lassi cost at our resort. While tipping isn't the norm in this country, it's appreciated so we had chosen to tip the equivalent of $1 for each lunch and dinner, but that seemed insultingly high on a bill that small! In a country where the average monthly wage is roughly $50 in cities and as low as $15 in the poorer countryside, a $1 tip is about half a day's wages! Plus it goes more directly to the worker. We had read in the Thailand guidebook that the government figured that while backpackers don't spend as much on a daily basis as package tourists, they stay longer and spend their money in more remote, i.e. poorer, areas. Which brings me back to my dilemma -- who is that $2 drink at the resort really benefitting? Probably not the workers. And why pay that much when a similar drink could be had for 1/2 to 1/3 the price? Maybe the mango lassi is a bad example, but an iced coffee with milk is 20,000 dong at the resort versus 6 - 8,000 dong down the street at a local's restaurant. OK, I'll step off my soapbox now.

|

|

|

h: I had been, a little at a time, reading up on the history of Vietnam in the Lonely Planet guidebook. I was finding it far more interesting than Thailand because, well honestly, unlike Thailand, Vietnam's history involves invading Westerners. It seems everyone in this part of the world, Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, have all had an endless string of conflicts among themselves throughout history and prehistory, and in addition many have also had invasions from colonizing westerners as well as the Chinese to the north. Thailand was the only country in the region to escape colonization by Westerners, but it had plenty of internal and neighboring conflicts. Malaysia got the British. Vietnam got the French.

Have you ever had the experience of picking up slivers and slices of information on a given subject but you aren't even always aware that this information is related until at some point you took that one course or read that one book or saw that one television program that connected all the dots for you? For me, this trip to Vietnam was it. Stars of unassociated information in the night sky of my mind slowly began to form constellations.

I changed school districts three times during the course of my education and I am keenly aware that what suffered as a result of that is my comprehensive knowledge of history. I had history year after year but somehow always managed in shifting curriculums to miss world history and get yet another year of American history. In light of that, you would think I would know my American history inside and out but surprisingly American history is an unnecesarily thick textbook and each year we would start at the beginning and make our way through as far as the Civil War before the school year would end. So far as I understood in any depth, America had only really participated in two wars - one that had something to do with taxes on tea and the other having something to do with black people. War has never particularly interested me as a subject and I had done little to supplement my swiss-cheese history education.

First of all, I had seen probably ten years ago a film called Indochine with Catherine Deneuve. A story of a relationship between a mother and adopted Vietnamese daughter and their love affairs with the same man (ah! the French!), it is set during the fall of French Colonialism in the early part of the Twentieth Century. I had been swept away by the scenery and romance, but I had never actually placed the geography or chronology.

And then in college I'd been assigned to read a book called Dispatches by Michael Herr. It was about the war in Vietnam, a journalist's perspective, but our study of the work focused on the writing style. In retrospect, the professor probably selected the work because of how this style, a stream-of-consciousness fluidity, had been applied to a subject so brutal and disjointed as war. In light of the author's choice in using this style, his emphasis was not on the linear progression of events; it was on impressions and reactions and deeply subjective. So again I managed to skirt my way around any real knowledge of this war in Vietnam. Heck, I've never even seen Apocolypse Now or Born on the Fourth of July.

But travelling in Vietnam and reading the pages that summarize the French and American involvement in Vietnamese history left me unable to ignore anymore this segment of my country's history - especially at a time when the newspapers are splashed with articles comparing current events in Iraq with those that launched our troops into Vietnam. To read my transcribed version of the Lonely Planet Vietnam's version of history in a new browser window, click here.

Last September Jan and I did a trip to Spain and for one all-too-brief night we stayed in a small town called Ronda in a lovely and overpriced hotel that was said to have been home to Hemmingway as he wrote For Whom The Bell Tolls. Since this trip I had been meaning to read this work and had found a copy in Australia which I read in Thailand. Set in the Spanish Civil War, the story follows an American who has been sent to blow up a bridge as part of an offensive operation. He must recruit guerillas in the hills to aid him and this forms the climax of the story; the bridge has been ordered to be blown at first light. If the bridge could be blown at night then the guerillas could escape. But as the geography exists, there is nowhere for them to go really in daylight and blowing the bridge becomes somewhat of a suicide mission. We spend four days with our main character, the American, and little by little come to understand why this American has chosen to fight in the Civil War of a country that is not his own, and in many ways why any man has chosen to fight in any war. I am not keen on war as a setting for my fiction, but the novel was so well written when our hero dies courageously at the end, I cried. Some things about war had been illuminated for me and although I was not persuaded it is right, the character is impressively written enough that I couldn't help by empathasize with his choices and plight. You see, Hemmingway elegantly explores how wars don't come in black and white but in endless shades of gray - who is fighting for what and allied with whom and to serve what purpose.

When we arrived in Vietnam, I read in the guidebook also about the War Remnants Museum Jan mentioned. It was listed as the top attraction for foreign tourists in Saigon and it detailed some of the exhibits, including photos of the infamous My Lai Massacre, tiger cages used to house Viet Cong, photos of babies deformed from chemical weaponry, and photos of scenes of torture. I was immediately squeamish but felt an obligation to go and see what my country had done. I persuaded Jan that I wanted to see it at the end of my stay in Saigon as I knew it would depress me terribly and didn't want to spoil my time in this beautiful city, so we planned it for the last day of touring in Saigon for the afternoon. After the Reunification Palace tour.

As Jan mentioned, we never made it there. The Reunification Palace tour is, in and of itself, communist euphemism. The tour is loaded with propaganda and paints the Americans as the bad guys and revels in the glory of a reunited Vietnam. This is all reasonably transparent and somewhat disgusting. But the trouble is that even when you can see through the thinly veiled communist propoganda, you are still left with the horrors of the American government's involvement in this country's war. At the end of the tour there is an air-conditioned room full of photographs that are supposed to tell the story of the history of Ho Chi Minh City and it's path to the glory of its present government. Mostly the room is full photographs of men in suits shaking hands, dignitaries of various periods doing what dignitaries do. On one wall, however, there was a series of photographs of events that took place shortly before the Reunification Palace became such. The infamous photo of a monk who had lit himself on fire to protest the anti-Bhuddist policies of a leader who had been installed into power by the American government. I tell you I stood there and looked at that image, a man sitting peacefully while his very living flesh charred before me and I wanted to vomit. We came out of the palace and I was crying; I told Jan that despite all he had done to accomodate my request regarding the visit to the War Museum and the fact that I felt an obligation, that I didn't want to go at all. Having been the lazier of the two of us with regards to seeing all there is to see in a given place, I expected him to put up a fight. He didn't. I don't think there's much more to say than that.

As Jan mentioned, we never made it there. The Reunification Palace tour is, in and of itself, communist euphemism. The tour is loaded with propaganda and paints the Americans as the bad guys and revels in the glory of a reunited Vietnam. This is all reasonably transparent and somewhat disgusting. But the trouble is that even when you can see through the thinly veiled communist propoganda, you are still left with the horrors of the American government's involvement in this country's war. At the end of the tour there is an air-conditioned room full of photographs that are supposed to tell the story of the history of Ho Chi Minh City and it's path to the glory of its present government. Mostly the room is full photographs of men in suits shaking hands, dignitaries of various periods doing what dignitaries do. On one wall, however, there was a series of photographs of events that took place shortly before the Reunification Palace became such. The infamous photo of a monk who had lit himself on fire to protest the anti-Bhuddist policies of a leader who had been installed into power by the American government. I tell you I stood there and looked at that image, a man sitting peacefully while his very living flesh charred before me and I wanted to vomit. We came out of the palace and I was crying; I told Jan that despite all he had done to accomodate my request regarding the visit to the War Museum and the fact that I felt an obligation, that I didn't want to go at all. Having been the lazier of the two of us with regards to seeing all there is to see in a given place, I expected him to put up a fight. He didn't. I don't think there's much more to say than that.

Lonely Planet's account is not exactly unbiased in its description of the American War in Vietnam, but considering the complexity of the events I have a hard time imagining that there is an unbiased description out there. In fact, in retrospect I can see why one history teacher after another never made it to the events of this war - who wants to throw themselves to the sharks, parents outraged in a school-board controversy by trying to present 'the facts' on something which to this day divides the American public, albeit silently? And finally, the penny drops. If I am so ignorant on this war, me who had the benefit of an academic family and a reasonably decent educational experience, how can I expect others of my generation to have any better information? How much of the American voting public is like me, too young to have lived through this war and not educated about it as a result of leftover controversy still unresolved by the generation of our parents?

My sources of information on what happened in Vietnam are still limited and thus I don't profess to know 'the facts' but as my stay in Vietnam has progressed I am more and more impressed with the resiliance of the Vietnamese people. As we climb into taxis and seat ourselves in restaurants it is a common question to answer, Where are you from? USA, I tell them. Never once has that produced anything negative. Perhaps the sentiment is still there in the older people, the ones who lived through it all and the youth that cleans our rooms and sells us fruit is not burdened with the scars of memory. But in the US, bitterness over the American Civil War dragged out for a century plus. And there are plenty of Americans who might read what I have written here and conclude that I side with a now nonexistent enemy that they fought 40 years ago. But my experience of the Vietnamese is that in this land where our government had no business in the first place, the people have recovered their good will towards America at what I consider to be a staggering rate. Policially speaking, pretty much everyone was in the wrong in some manner and the real tragedy is that the people of both nations are still living with the consequences of the decisions of their governments.

Times that Jan and I are in transit tend to be the times that I do my reading. The flight over from Bangkok to Saigon I consumed a copy of the International Herald Tribune and TimeAsia. A few days later as we took our bus out of Saigon I scoured another copy of the Tribune and also TimeEurope that had been left in a seat pocket, apparently by a German on holiday. The War in Vietnam is suddenly in the news again, this time as it is referred to by columnists and news analysts who are comparing events of late involving the US Presidency to those that happened so many years ago. It predictable that prospect of a war would dredge up the events of the past, but I am shocked at how quickly the anguish of how that war divided our country and the circumstances which brought it about in the first place could be forgotten so quickly by the American people. Vietnam veterans across the US to this day suffer from disabilities and ailments, physical and psychological, that they obtained as a result of fighting at the request of their government - a government which mislead them as to why they were fighting in the first place. Mothers lost sons, siblings lost brothers. Vietnam suffered greatly and that saddens me to see, but even greater it calls to mind the suffering of my own countrymen and the prospect of similar consequences which could easily result from this proposed war with Iraq. I cannot understand why the American President who repeatedly reminds us that he has sworn to protect Americans would so readily put them in harm's way when the rest of the entire world has vowed to support a peaceful resolution of this conflict with Iraq.

I am inclinded to lean Left in my politics; I am the quintessential bleeding heart liberal and I attribute it in part to my Catholic and lower-middle-income academic upbringing and also in part to my reproductive organs which as a woman tend to call for bringing life into the world rather than taking life out of it. If I was at home, I am reasonably sure that I would be of the same opinion that I am abroad: Bush is a white, upper-class man, in the back pocket of other white upper-class men who are silently running the world from the background. BUT. I've put some thought into it and as objectively as I can I've tried to consider whether any American could have travelled as I have for the last months, to Vietnam in particular, and not have their perspective altered considerably. I sent Keisling's letter of resignation to some friends of mine; one responded, much to my surprise, that he is not sure how he feels about attacking Iraq and has no position in being torn by both arguments. I suppose it is for him that I write this diatribe. He is the sort who is inclined to read up on his history, spend some time in pursuit of the facts, weigh information carefully before taking a stance and because of his reputation for diligence in this respect I would normally tend to be inclinded to trust his judgement before my own in many instances. So for him to suggest that he was persuaded in any way that the US should be responsible for taking apart this new evil empire left me stunned. It led me to ask myself what Americans are actually hearing from the domestic press and knowing my country's aversion to international news it occurred to me that perhaps I have had the benefit of a unique perspective in my travels over the last few months.

I have continued my quest for more news, more news, reading more English-published papers here abroad, watching CNN-Asia when I can, and occasionally jumping online to catch something here or there. Some interesting trends emerged and have yet to be broken, weeks later as I write this. Nowhere have I seen a story published or broadcast in favor of this war, in support of the American president. Nowhere. There is occasionally an opinion column which outlines what it thinks are acceptable terms for going to war or an article that describes Bush's justifications and so-called proof. And pretty much everyone seems to think that Saddam is a madman who needs to be stopped. But there are no articles written interviewing leaders in countries around the world that think this war is actually a GOOD idea. There are no articles about demonstrations being held protesting the cruelty and inhumanity of Saddam's reign of terror. We have met no foreigners, native to the countries we are visiting OR other travellers from Europe and Asia, who are in favor of this war. There is no political conversation to be tiptoed around here because everyone we meet is resigned and there is no discussion to be had - only sad, angry, silent agreement.

Communism was our enemy of the past; it was our position as Americans that the Communists were intent on taking over the world one step at a time and that this was not acceptable. It was our duty to stop them in order that we might preserve diversity in the world, we were told. Saddam is our enemy of new and once again our President calls on us as Americans to perform a service to our country and the world in fighting against evil and tyranny. I cannot help but question, however, how attacking Iraq in the face of UN and world disapproval, will differentiate us from the irresponsible leadership we seek to dislodge.

|

|

2.23.03 - 2.28.03

2.23.03 - 2.28.03

j: Hanging out and relaxing, oh yeah. We went for several meals at one little local restaurant where one of the waitstaff, named Miêu, was particularly helpful -- I dropped off our laundry there (cost US$1 per kilogram, not some inflated price per piece -- we didn't want a repeat of Bangkok), plus bought some fruit at the related street-side stand, plus he said we could walk through their place to see the nearby sand-dunes, plus of course I had to come back for dinner. The meals (for we returned several times) there were pleasant, and we were treated to a complimentary small plate of fruit for dessert, even the first night before we tipped. One night we even received 3 plates of different fruit! Hard to see what effect the consistent tipping had exactly, but we did notice that not every table received a little fruit plate. One evening Miêu helped me with my Vietnamese pronounciation, which of course did not match my phrasebook's pronounciation guide -- no wonder people had so much trouble understanding me! Well, that plus the whole tonal thing. Grrr.

One morning at 7am, while a sick Heather slept, I walked over there for a little guided tour with Miêu into the dunes behind the restaurant. The terrain was surprisingly varied, starting with a flat "plain" containing fishermen's shacks, then tan dunes rising up, followed by red dunes, another plain with some vegetation and a boy herding cows, followed by another set of dunes and finally another desert plain with again different vegetation going into the distance. Looking back towards the South China Sea, the first 200m of land up to the road was covered in palm trees and the hotels were mostly invisible. It soon became apparent why my guide wanted to leave so early instead of my suggested 9am -- it was darn hot! I had only had a snack and within a few minutes I was feeling light-headed with a nice headache coming on, despite the large water bottle in my hand. The sand had gotten into my shoes on the first tiring dune climb, and of course Miêu hadn't even broken a sweat (and was wearing flipflops to boot). By the time we returned to the restaurant a mere 45 minutes later, I was wiped. Miêu bought some pho for himself for breakfast, and even a bowl for me too, from the restaurant/stand across the street, plus an orange each from the fruit vendor in front of his restaurant. I'm not sure why he bought me breakfast, but he didn't ask for money for the little guided tour either, though of course I gave him a tip as planned. Yes, the Vietnamese people truly are friendly and helpful.

One morning at 7am, while a sick Heather slept, I walked over there for a little guided tour with Miêu into the dunes behind the restaurant. The terrain was surprisingly varied, starting with a flat "plain" containing fishermen's shacks, then tan dunes rising up, followed by red dunes, another plain with some vegetation and a boy herding cows, followed by another set of dunes and finally another desert plain with again different vegetation going into the distance. Looking back towards the South China Sea, the first 200m of land up to the road was covered in palm trees and the hotels were mostly invisible. It soon became apparent why my guide wanted to leave so early instead of my suggested 9am -- it was darn hot! I had only had a snack and within a few minutes I was feeling light-headed with a nice headache coming on, despite the large water bottle in my hand. The sand had gotten into my shoes on the first tiring dune climb, and of course Miêu hadn't even broken a sweat (and was wearing flipflops to boot). By the time we returned to the restaurant a mere 45 minutes later, I was wiped. Miêu bought some pho for himself for breakfast, and even a bowl for me too, from the restaurant/stand across the street, plus an orange each from the fruit vendor in front of his restaurant. I'm not sure why he bought me breakfast, but he didn't ask for money for the little guided tour either, though of course I gave him a tip as planned. Yes, the Vietnamese people truly are friendly and helpful.

On an unrelated note, about the movie Indochine... in Saigon, and as it turns out in Hanoi too, many places sell bootleg DVDs for 20,000 dong (US$1.33) and CDs for 10,000 dong (US$0.66), including our mini-hotel -- there was no lobby, just a DVD/CD shop on the ground floor. Anyways, we bought Indochine starring Catheine (sic) Deneuve because it was topical, as Heather already mentioned, and because we were curious if a "region 3" DVD would play on the laptop (it did, but it won't play on a stereo DVD player at home, which are region 1). On the back side of the sleeve copyright violators were warned that they would be "rosecuted" -- one of many funny typos. Some of the DVD sleeves even had the totally wrong description for the movie on the back side. One Vietnamese bottled water company is called "La Vie" and there are about 20 copies of it with slight name variations, but the look and feel of the logo right down to the colours are definitely copied. Ah yes, the Vietnamese are great at duplicating things -- more to come on some legal copying later.

One afternoon a small MTV video crew was at our resort taping a famous -- though not to me -- Vietnamese singer named My Linh, doing a video for her forthcoming mostly-English-language CD. They asked a number of us lounging about to dance in the background behind her, mouthing the chorus when it comes. About seven of us did this -- a cute Australian honeymoon couple, 3 of the 4 Italians, the kitesurfing-dude resort owner and myself. I suggested beer might help loosen up the dancing, and promptly a tray of Fosters appeared, courtesy the MTV crew. It all felt a little stiff and awkward, and what we thought was a trial run turned out to be the real thing. We were told that this video would be edited up from scenes taped in several locations in Vietnam and the USA, and should be on TV this summer. The song is called "Let's Do It Again" I believe. In the next take (without us), My Linh was dancing/singing in the surf and fell into it -- though I doubt that will make it into the video! We had already met the Aussie couple before this, but the bonds strengthened. As for the Italians, I spent some time talking to these nice people too over the next few days. And lastly, we did see some CDs of hers in stores, and I asked a handful of Vietnamese people if they had heard of her -- they all had, as she has sold millions of CDs there -- and showed them the photo of myself with My Linh to their astonishment.

One afternoon a small MTV video crew was at our resort taping a famous -- though not to me -- Vietnamese singer named My Linh, doing a video for her forthcoming mostly-English-language CD. They asked a number of us lounging about to dance in the background behind her, mouthing the chorus when it comes. About seven of us did this -- a cute Australian honeymoon couple, 3 of the 4 Italians, the kitesurfing-dude resort owner and myself. I suggested beer might help loosen up the dancing, and promptly a tray of Fosters appeared, courtesy the MTV crew. It all felt a little stiff and awkward, and what we thought was a trial run turned out to be the real thing. We were told that this video would be edited up from scenes taped in several locations in Vietnam and the USA, and should be on TV this summer. The song is called "Let's Do It Again" I believe. In the next take (without us), My Linh was dancing/singing in the surf and fell into it -- though I doubt that will make it into the video! We had already met the Aussie couple before this, but the bonds strengthened. As for the Italians, I spent some time talking to these nice people too over the next few days. And lastly, we did see some CDs of hers in stores, and I asked a handful of Vietnamese people if they had heard of her -- they all had, as she has sold millions of CDs there -- and showed them the photo of myself with My Linh to their astonishment.

And lastly, speaking of music, one night we ended up at an Aussie-owned-and-themed restaurant that the honeymooners had suggested, which was ok but didn't deliver on the hot-coals-on-the-table type of dish we had expected. I bring it up because of the strange assortment of music they played, including one Muppets song -- a remake? -- of a Muppets sketch I vividly remember from my childhood. There aren't any words, as the drummer Animal is the throaty singer who belts out a few nonsense syllables ("ma num na na") after the chorus of chickens sings the background sounds ("do doo de do doo"). What made the sketch funny was that Animal kept walking off the stage, but the music and chicken-led chorus would start up again, and he'd come running back to the microphone to sing his 4 syllables, each time from further away. Heather had never seen the sketch, but it has become a running inside joke in the trip, as we randomly would sing those 4 or 5 syllables.

h: Mui Ne is a mostly a bright, sweaty blur for me; I have some images of ruffles of bougainvilla, blinding white sand, and water a color of green that people try to describe as sea-green or jade but there is no description for the color of this water. It was truly unique. But aside from that, I was out of commission pretty much the whole week we spent at Mui Ne. I had felt something coming on for a few days, you see, and the day we arrived at the beach I had a sore throat which progressed into a strange sort of cold and flu that dragged on for a week... plus. And, because this is the part of the story that you have all been reading so diligently for, I also had not fully recovered from my food poisoning spell in Ko Samet. I was still having diarrhea off and on (charmed, I'm sure) and could not be certain if it was caused by a nagging parasite or merely the side effects of the malaria drug I'd been taking for over a month now. This headcold as it was, the first three days at Mui Ne are particularly hazy and I can't recall much beyond dragging myself up to the road outside the resort for two meals each day. I dreaded each meal, both because the food offered no comfort and because I seemed to have an amazing talent for being the one who finds the hair or insect in my entree. I had noticed this particular magnetism of mine much earlier on in the trip - starting perhaps in Khao Sok, our jungle hike in Thailand, where I was the only one to get a toy surprise at the bottom of our fried-rice luncheon... a fairly entact giant cicada wing. And from time to time as we sat in restaurants in Thailand I would find a hair or a fly or both in something. Sometimes I would make comment, sometimes not. I would never send the food back, figuring that it would only come back out again minus the extras and I could do that perfectly well myself. You see, having worked in restaurants taught me that one customer's complaint of a foreign body in their food is unlikely to reform kitchen sanitation habits in an instant.

h: Mui Ne is a mostly a bright, sweaty blur for me; I have some images of ruffles of bougainvilla, blinding white sand, and water a color of green that people try to describe as sea-green or jade but there is no description for the color of this water. It was truly unique. But aside from that, I was out of commission pretty much the whole week we spent at Mui Ne. I had felt something coming on for a few days, you see, and the day we arrived at the beach I had a sore throat which progressed into a strange sort of cold and flu that dragged on for a week... plus. And, because this is the part of the story that you have all been reading so diligently for, I also had not fully recovered from my food poisoning spell in Ko Samet. I was still having diarrhea off and on (charmed, I'm sure) and could not be certain if it was caused by a nagging parasite or merely the side effects of the malaria drug I'd been taking for over a month now. This headcold as it was, the first three days at Mui Ne are particularly hazy and I can't recall much beyond dragging myself up to the road outside the resort for two meals each day. I dreaded each meal, both because the food offered no comfort and because I seemed to have an amazing talent for being the one who finds the hair or insect in my entree. I had noticed this particular magnetism of mine much earlier on in the trip - starting perhaps in Khao Sok, our jungle hike in Thailand, where I was the only one to get a toy surprise at the bottom of our fried-rice luncheon... a fairly entact giant cicada wing. And from time to time as we sat in restaurants in Thailand I would find a hair or a fly or both in something. Sometimes I would make comment, sometimes not. I would never send the food back, figuring that it would only come back out again minus the extras and I could do that perfectly well myself. You see, having worked in restaurants taught me that one customer's complaint of a foreign body in their food is unlikely to reform kitchen sanitation habits in an instant.

At any rate, I'd noticed this trend but hadn't bothered to say anything to Jan about it for quite some time seeing as how it would just sound exaggerated, like I was complaining. But in Saigon I finally said something and it was in Mui Ne that we really put it to the test. Two idential bowls of pho set before us and the one I choose? You guessed it: giant black hair mixed in with the noodles. The same with stir-fried entrees - Jan and I could be eating off the same plate and I would pick up the vegetable with the hair affixed to the bottom and he would be fine throughout the meal. I held such attraction for these foreign objects that even Jan, my witness in the regularity of these events, had come to tease me that he had only brought me on the trip to ensure his food would be pure and unspoiled.

As Jan mentions, we took to patronizing this singular cafe and they were very friendly to us there. Even the music, Willie Nelson's Greatest Hits on Hawaiian Guitar, was soothing and pleasant. We showed up for lunch one day only to discover that they were hosting a group from one of the open-ticket tour buses for lunch. The tables were all full but our hostess recognized us and somewhat forcibly seated us at a table with a single man from the bus, much like one might do in a train car or the like. Our conversation with the man started off well enough - he was from Los Angeles and was travelling to Nha Trang from Saigon... he was interested that they kept at a cat at this particular restaurants since most Vietnamese didn't seem to keep cats, he told us. He had this East Coast demeanor and nasal voice that made him seem a little used-car salesman to us reserved West-Coasters, but he was pretty charismatic and conversational and we were grateful to have someone to talk to that didn't require us to leave the articles and prepositions out of our sentences. He seemed to be trying awfully hard to indicate to us that he was no greenhorn at being a visitor to Vietnam, which was kind of annoying but not particularly strange. Jan politely went with the cue and asked if he was travelling on holiday or business. He said that he hoped to do a little of both, maybe. So again, Jan snapped at the carrot dangled before him and asked what sort of business. He leaned back in his chair and looked both of us in the eye and cracked open a rather large toothy smile. He said, "Well, it's kind of immoral actually."

As Jan mentions, we took to patronizing this singular cafe and they were very friendly to us there. Even the music, Willie Nelson's Greatest Hits on Hawaiian Guitar, was soothing and pleasant. We showed up for lunch one day only to discover that they were hosting a group from one of the open-ticket tour buses for lunch. The tables were all full but our hostess recognized us and somewhat forcibly seated us at a table with a single man from the bus, much like one might do in a train car or the like. Our conversation with the man started off well enough - he was from Los Angeles and was travelling to Nha Trang from Saigon... he was interested that they kept at a cat at this particular restaurants since most Vietnamese didn't seem to keep cats, he told us. He had this East Coast demeanor and nasal voice that made him seem a little used-car salesman to us reserved West-Coasters, but he was pretty charismatic and conversational and we were grateful to have someone to talk to that didn't require us to leave the articles and prepositions out of our sentences. He seemed to be trying awfully hard to indicate to us that he was no greenhorn at being a visitor to Vietnam, which was kind of annoying but not particularly strange. Jan politely went with the cue and asked if he was travelling on holiday or business. He said that he hoped to do a little of both, maybe. So again, Jan snapped at the carrot dangled before him and asked what sort of business. He leaned back in his chair and looked both of us in the eye and cracked open a rather large toothy smile. He said, "Well, it's kind of immoral actually."

This certainly got our attention. Oh, we asked smiling too broadly in return, as if we were part of the joke. How so?

It seems this fine American was seeking a country to manufacture air guns to sell in the States, really high-powered air guns that could do some serious damage - I forget how he put it but it was something like that. You see, he told us, some gun control bill passed in recent years (he couldn't be sure which one) apparently had included a loophole clause that excluded air-powered rifles from being federally regulated. His brother, I think he told us, had noticed this loophole and had the idea of manufacturing some heavy duty rifles that could not be regulated since they use only air power and now they were sort of looking for someone to manufacture such a thing. We asked why not China, but he informed us that apparently it's getting quite expensive to manufacture things in China and that Vietnam is a much better way to go. They have factories here where they can manufacture these sorts of machines, he said, you know from the wars and from their automobile plants. That sort of thing. Now, I do not present any of this as truth - merely what we were told by this man. Based on his demeanor, his inability to answer our cautious questions in detail, and the fact that self-professedly he is not the brains of the operation, I was not terribly persuaded that this man would be putting high-powered air rifles into the hands of unregisterered 15-year-olds anytime soon. Still it was an interesting reminder that these sorts of loonies are out there and they have passports. If this brother of his conceived of such a plan, however half-assed, then certainly so will others. His tour bus stopped in front of the cafe and he gathered his things to climb back on board; he cordially wished us good continued travels as he hoisted his pack. Somewhat stunned and relieved to see him go, we waved our goodbyes back and as we watched him board the bus Jan smiled falsely and said in a low voice from the corner of his mouth, "I hope your business venture fails." I could not hold back a laugh. My thoughts exactly. What a jerk.

It seems this fine American was seeking a country to manufacture air guns to sell in the States, really high-powered air guns that could do some serious damage - I forget how he put it but it was something like that. You see, he told us, some gun control bill passed in recent years (he couldn't be sure which one) apparently had included a loophole clause that excluded air-powered rifles from being federally regulated. His brother, I think he told us, had noticed this loophole and had the idea of manufacturing some heavy duty rifles that could not be regulated since they use only air power and now they were sort of looking for someone to manufacture such a thing. We asked why not China, but he informed us that apparently it's getting quite expensive to manufacture things in China and that Vietnam is a much better way to go. They have factories here where they can manufacture these sorts of machines, he said, you know from the wars and from their automobile plants. That sort of thing. Now, I do not present any of this as truth - merely what we were told by this man. Based on his demeanor, his inability to answer our cautious questions in detail, and the fact that self-professedly he is not the brains of the operation, I was not terribly persuaded that this man would be putting high-powered air rifles into the hands of unregisterered 15-year-olds anytime soon. Still it was an interesting reminder that these sorts of loonies are out there and they have passports. If this brother of his conceived of such a plan, however half-assed, then certainly so will others. His tour bus stopped in front of the cafe and he gathered his things to climb back on board; he cordially wished us good continued travels as he hoisted his pack. Somewhat stunned and relieved to see him go, we waved our goodbyes back and as we watched him board the bus Jan smiled falsely and said in a low voice from the corner of his mouth, "I hope your business venture fails." I could not hold back a laugh. My thoughts exactly. What a jerk.

Jan soaked up the sun, I slept and slept and slept. My dreams were vivid and colorful both by day and by night. With a gecko and ceiling fan for company, I had plenty of time to contemplate the meaning of life, the purpose of travel, and why the sleek lines of the interior of our room held such appeal for me. I watched a Sting DVD over and over again, I monitored the progress of my lungs, nose, and bowels, and I took many many showers. If I hadn't had some good reading material, I would have lost my mind. We stayed three extra days at the beach and had to skip our trip to Dalat as a result. By the time we left, I was still a little shaky but definitely ready to get out of smallsville. The beach was lovely and I am sure I'll return, but being stuck at the beach when you're sick and can't enjoy it is torture.

|

|

|

2.29.03

j: To Hoi An. Not to be confused with Hanoi, also written as Ha Noi -- a little like Tokyo vs Kyoto, except only one is a big city. After saying farewell to our newfound friends at the resort, we dragged our bags down the road to our little restaurant to eat lunch and await the bus to Nha Trang (US$6, 4hr or so). Nha Trang is a larger town further up the coast, home of the best municipal beach in Vietnam, and full of nightlife and crime, especially theft. When the bus pulled into town, the same old "we'll take you to a few hotels" scheme appeared, albeit this time with lots of warnings about the theft. Overall it sounded like a frat-boy-party scene in the town, so we decided to head to the train station to catch a night train to Hoi An -- which ironically was our original plan before Heather became ill, but she was feeling well enough to choose the night train. We hopped off the bus while some fellow travellers checked out the first hotel choice, and headed down the street to two waiting taxis. Well, is a taxi a taxi without a taxi driver? Some man on a second or third floor window saw us standing there clueless, yelled into the dark distance (it was early night already) and lo and behold our driver appeared. He opened the trunk, giving us a splendid view of the foursome of cucarachas that dispersed, which he vainly tried to knock out of the trunk. Sigh.